How the Aral Sea died: One of the greatest environmental disasters of the modern era

Once a thriving inland sea supporting vibrant communities, bustling fisheries, and rich biodiversity, the Aral Sea has transformed into a largely barren desert within just a few decades. The disaster traces back to Soviet-era irrigation policies that drastically diverted the region’s rivers for cotton farming.

As water inflow dwindled, the sea shrank at a staggering rate, leaving behind toxic dust, abandoned ports, and ruined livelihoods. Today, the Aral Sea symbolizes not only environmental loss but also the socioeconomic consequences of unsustainable development. Understanding how this catastrophe unfolded offers valuable lessons for global water management and climate resilience in the twenty-first century.

From thriving lake to shrinking shorelines

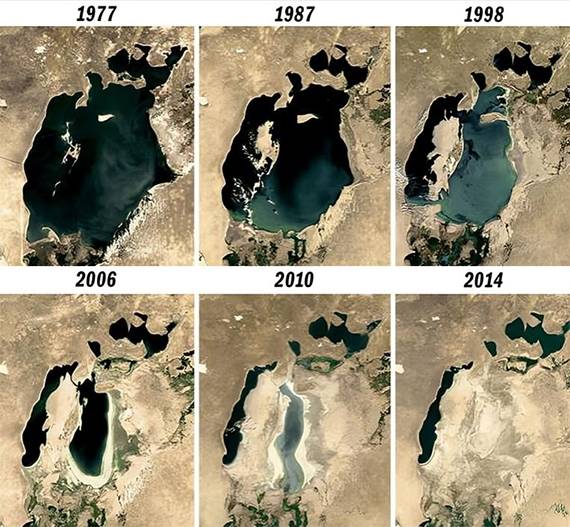

Half a century ago, the Aral Sea was the fourth-largest lake on Earth, spanning more than 67,000 square kilometers. Throughout its long history, the size of the Aral Sea naturally fluctuated as rivers shifted their courses or climatic conditions changed. However, these fluctuations were nothing compared to the dramatic decline that began in the 1960s.

As Soviet planners expanded cotton production across Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, enormous volumes of water were diverted from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers. The lake’s primary sources of inflow were effectively redirected into irrigation canals, leaving the Aral Sea without the water it needed to balance natural evaporation. By the 1980s, the effects were unmistakable: shrinking shorelines, rising salinity, and collapsing ecosystems.

How irrigation policies contributed to the disaster

The large-scale irrigation projects built during the Soviet era were designed to transform Central Asia into a cotton-producing powerhouse. While these policies boosted agricultural output, they failed to consider long-term environmental sustainability. Water loss from unlined canals, inefficient irrigation methods, and overuse of river resources all contributed to the rapid drying of the Aral Sea.

Groundwater, rainfall, and snowmelt could not compensate for the massive withdrawals upstream. For years, the scale of the disaster was concealed from the public, only becoming widely known in the mid-1980s when Mikhail Gorbachev’s reforms revealed the true extent of environmental degradation. Despite the alarming findings, water withdrawals continued, accelerating the collapse of the sea.

Fragmentation of the Aral Sea

By the late 1980s, the Aral Sea had split into two separate bodies of water: the Small Aral in the north and the Large Aral in the south. The southern portion continued to deteriorate rapidly, eventually dividing again into eastern and western basins. By 2007, the Large Aral had lost almost 90% of its original volume, dropping from 708 cubic kilometers to just 75. Salinity levels skyrocketed from 14 grams per liter to about 100, making the water inhospitable to nearly all native species. The retreat of the shoreline was dramatic, receding nearly 100 kilometers from former ports like Aral’sk. Much of the southern basin has now become the Aralkum Desert, a barren landscape where ships once sailed.

Toxic residue from decades of agriculture

As the lake dried, it exposed a vast seabed contaminated with pesticide residues and agricultural chemicals from decades of intensive farming. These pollutants settled into the soil and are now carried by strong winds across the region. The toxic dust contributes to respiratory illnesses, throat and lung infections, birth defects, and cancers among people living in surrounding communities. More than 54,000 square kilometers of lakebed have become a hazardous source of airborne contamination, affecting both human health and agricultural productivity.

Collapse of local ecosystems and fisheries

The once-thriving ecosystems of the Aral Sea region have nearly vanished. River deltas that depended on seasonal flooding have dried up, leading to the collapse of agriculture in areas once considered fertile. Of the 32 fish species that originally inhabited the lake, only six remain, and even these survive primarily in small, isolated northern sections. The demise of commercial fishing devastated local economies. In the early 1960s, fishermen harvested about 40,000 tonnes of fish each year. With the rise in salinity, species began disappearing one by one, including the resilient Black Sea flounder, which vanished from the Large Aral in 2003. The loss of fisheries eliminated roughly 60,000 jobs, forcing many families to migrate in search of work.

Desertification and regional climate change

The transformation of the Aral Sea into the Aralkum Desert has drastically altered the region’s climate. With less water to regulate temperature, summers have become hotter, winters colder, and rainfall less frequent.

Dust storms now occur more often, carrying salt and chemicals across hundreds of kilometers. Vegetation has largely disappeared, replaced by sparse, salt-resistant grasses. The populations of birds and mammals have dropped by nearly half as habitats continue to degrade. Local communities face increasing difficulty accessing fresh water, and agriculture suffers from poor soil quality and frequent drought.

The dark history of Vozrozhdeniya Island

One of the most troubling chapters in this environmental disaster involves Vozrozhdeniya Island, once located in the middle of the Aral Sea. During the Soviet era, it served as a secret testing site for biological weapons. A small, isolated town housed laboratory workers conducting experiments on dangerous pathogens. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the island—now connected to the mainland due to receding waters—was abandoned. Looting left buildings stripped, but hazardous materials remained, adding another layer of environmental and public health risk to an already devastated region.

Lessons from the Aral Sea catastrophe

The disappearance of the Aral Sea is a powerful reminder of how unsustainable water management, political priorities, and short-term agricultural gains can lead to irreversible ecological damage. Restoring the entire lake is no longer considered feasible, but ongoing efforts in the northern region demonstrate that partial recovery is possible with responsible policies and international support. The Aral Sea disaster continues to influence global conversations about water security, environmental planning, and the urgent need for sustainable development.

Yorumlar

Kalan Karakter: